The Five-Day Workweek Is Dying

And the implications for work and cities are going to be fascinating.

Sign up for Derek’s newsletter here.

America is slowly returning to normal. Stadiums are packed. Travel has bounced back. Restaurant reservations are surging.

But even as they resume normal leisure activities, many Americans still aren’t going back to the office. According to data from Kastle Systems, which tracks building access across the country, office attendance is at just 33 percent of its pre-pandemic average. That’s lower than in-person attendance in just about any other industry for which we have good data. Even movie theaters—a business sometimes written off as “doomed”—have recovered almost twice as much.

What once seemed like a hot take is becoming a stone-cold reality: For tens of millions of knowledge-economy workers, the office is never coming all the way back. The implications—for work, cities, and the geography of labor—will be fascinating.

In the past few months, I’ve noticed that tech, media, and finance companies have basically stopped talking about their full return-to-office plans. And I’m not the only one. “I talk to hundreds of companies about remote work, and 95 percent of them now say they’re going hybrid, while the other 5 percent are going full remote,” Nick Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford University, told me. The exceptions to the rule, such as Goldman Sachs, are scarce.

“The number of person-days in the office is never going back to pre-pandemic average, ever,” Bloom told me. After two years of working from home, he said, employees don’t just prefer it. They also feel like they’re getting better at it. Despite widespread reports of burnout, self-reported productivity has increased steadily in the past year, according to his research.

In the next decade, U.S. workers will spend about 25 percent of their time working from home, Bloom says. That’s 20 percentage points higher than the pre-pandemic figure, leaving companies with an important choice: sign for significantly less office space, or accept that significantly more of your space will go unused on a given day.

Bloom is betting strongly on the latter. “Office occupancy has plummeted, but corporate demand for office space is down only about 1 percent,” he said. “That might sound shocking, but it’s because so many companies planning for hybrid work are expecting most of the office to be in on some days of the week, so they can’t shrink their space.”

Not every city is facing the same level of office abandonment. Occupancy rates in Houston, Austin, and Dallas have substantially and consistently outpaced those of coastal cities like New York and San Francisco. One plausible explanation is that remote work is partially sustained by COVID caution, and southern cities have a more laissez-faire attitude toward the pandemic than the bluest of the blue metros.

I should stress that the majority of Americans still cannot and do not work remotely. But I’ve come to see the remote-work revolution as akin to a cannonball dropped in a lake—an acute phenomenon whose ripples can warp every corner of the labor force. Let’s take a look at three major implications of this long-term shift in office work.

1. The five-day workweek is dying.

I know that sounds like a dramatic prediction. But follow the bread crumbs.

According to Bloom’s research, the most popular model of hybrid work has employees in the office Tuesday through Thursday. “This model, with Friday through Monday out of office, is hugely attractive to new hires, and it’s become a key weapon for companies,” he said. “It’s not that everybody gets a four-day weekend, but rather it gives them flexibility to travel on Fridays and Mondays, while continuing to work.”

For some knowledge workers, Friday through Monday may come to occupy a murky space between weekday and weekend—a sort of work-play purgatory, where the once-solid walls between work and life become more porous. “Mondays and Tuesday are the fastest-growing days of the week for travel,” Airbnb’s chief executive, Brian Chesky, told me. “More people are treating ordinary weekends like long holiday weekends.” In short, the typical five-day workweek may dissolve into something stranger and less settled—a three-day office week that exists within a longer work week.

But that’s not all. Bloom told me that he’s also seeing signs of remote-work envy from people who can’t do their jobs from home. “There is real resentment among workers who don’t have this cushy work-from-home deal but all their white-collar friends do,” he said. “I’ve talked to hospitals whose shift workers would rather work longer hours for four days than fewer hours for all five.”

Add it up—three days in the office for tech and media workers; four days in-person for hospital staff—and the five-day workweek seems endangered. Bloom suggested that schools might respond to these changes by offering teachers Monday or Friday off, which could be the nail in the coffin of the old-fashioned workweek.

This is all a bit speculative, and I can already see how these changes will be celebrated by some (Summer Fridays forever!) and problematic for others (Wait, what do I do if my kid’s school cancels Friday classes forever?). But the big-picture prediction is plausible: If the five-day office week is a goner for knowledge workers, the consequences could touch every corner of the labor market.

2. The age of hybrid work is going to be a beautiful mess.

When the internet disrupted brick-and-mortar stores, the response from many retailers was: Make shopping an experience. Now the internet has disrupted brick-and-mortar offices, and the response from companies may be similar: Make the office an experience.

“The one great advantage of the office is that it meets our tremendous desire for human contact,” Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at New York University, told me. If people are going to come back to the office multiple days a week, Moss said, the office will have to adapt. “Successful new offices will be like vertical yachts,” he said, “an experience that people seek out, with terraces, and outdoor areas, and fancy gyms, and places to eat.”

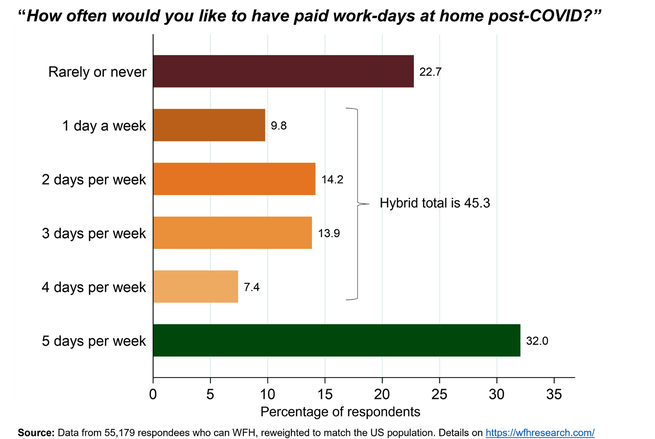

But “yachtifying” the office—even if such a thing is broadly possible—won’t be enough. Return-to-office preferences are all over the place, and any one-size-fits-all policy is going to make a lot of people upset. According to Bloom’s survey data, more than 20 percent of respondents would prefer to work from home “rarely or never,” while more than 30 percent say they would prefer to stay home for the entire workweek. The most popular hybrid solution for employers—three days in the office for everybody—is the preference of just 14 percent of workers.

When the office was the nucleus of white-collar work, there were problems. When the office stops being the nucleus of work, there will still be problems—just different ones.

Many young college graduates starting careers in remote companies without routine physical gatherings might miss the social glue that comes from being in an office. “My sense from the anecdotal evidence is that young workers are worried about the lack of such connections,” said Lawrence Katz, a professor of economics at Harvard University. “Difficulties in forming connections with peers and mentors generates a sense of drift for many new employees, leading them to be more open to moving jobs.” When the office is a place, there is a physical connection to colleagues. When the office becomes a group chat punctuated by Zoom all-hands meetings, switching jobs is practically as easy as logging out of one Slack account and logging into another.

Many employers are going to struggle through the transition to hybrid work. If they push too hard to get workers to come into the office, some people will just leave to preserve their independence. If employers fail to build any kind of tangible corporate culture, a lot of workers, feeling no sense of real community among their colleagues, will switch jobs with greater frequency. And whatever employers do, in an era of record-high job openings, a lot of workers will switch jobs anyway. The decline of the office is going to be messy for many companies, no matter what.

3. Cities are already starting to freak out.

If office occupancy never recovers, downtown areas will experience an extended ice age. Emptier offices will mean fewer lunches at downtown restaurants, fewer happy hours, fewer window shoppers, fewer subway and bus trips, and less work for cleaning, security, and maintenance services. This means weaker downtown economies and less taxable income for cities.

For this reason, some of the most outspoken advocates for return-to-office these days aren’t chief executives, but rather politicians and state officials. “Business leaders, tell everybody to come back,” New York Governor Kathy Hochul said earlier this month. “Give them a bonus to burn the Zoom app.” New York City Mayor Eric Adams echoed those remarks. “New York City can’t run from home,” he said. “It’s time to get back to work.”

In New York, Boston, and San Francisco, subway ridership could be permanently depressed. That means that transit authorities might never recover from their pre-pandemic highs, and downtown areas might never recover the lost foot traffic from weekday shoppers. Sarah Feinberg, who served as interim president of the New York City Transit Authority until 2021, told me over email that she’s worried not only for the transit authority’s finances but also for the soul of the city.

“It is important for offices to reopen and for white-collar workers to start commuting again,” Feinberg said. Remote work might be “good for the individual,” she added, but “we are in a very dark place if the only people who use transit are the people who actually have to show up to work in person, and the only places that make employees show up in person are the places that employ physical labor. That’s not a city I want to live in.”

It is, however, a city that many people want to live in. Rents in the New York area are skyrocketing, as people pour into Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Hoboken. A remote-work New York will not be the same place it was in 2019. Residential neighborhoods will bustle throughout the week, while Wednesdays in Midtown will feel like Sundays in Midtown used to. Some Manhattan offices will transform into apartments, alleviating the island’s housing crisis, while transit presidents will feel pressured to raise ticket prices, sadly punishing the low-income in-person workforce. The point is not that these things are all good or all bad but precisely that they are complicated. Americans really, really don’t want to go back to the office, and we are just beginning to feel the repercussions.