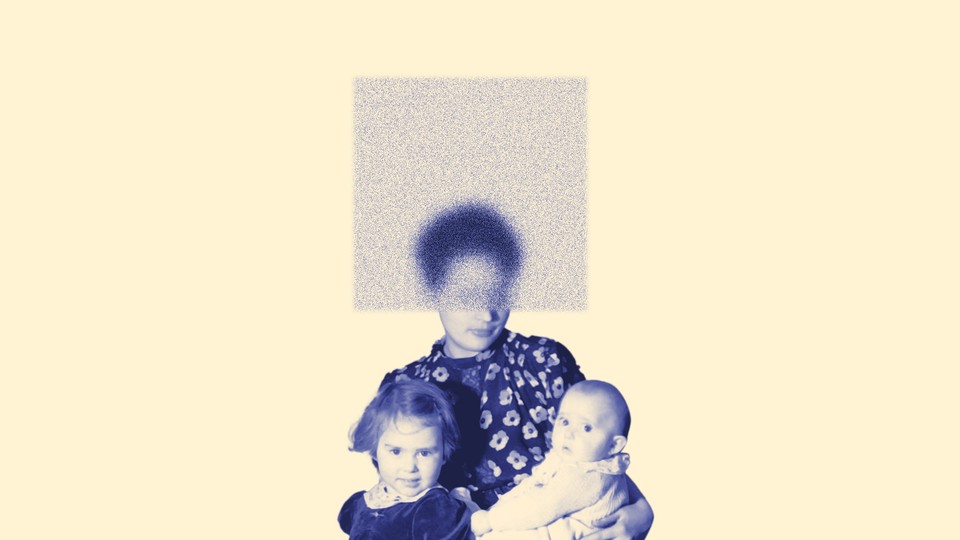

‘Mom Brain’ Isn’t a Joke

When our culture makes fun of mothers’ forgetfulness, it is abdicating responsibility for the overwork women are experiencing and its effects on their health.

You may have seen it on TV, in your workplace, or at school drop-off. Maybe you’ve had firsthand experience, been warned of its impending arrival, or met someone who’s had it themselves. It’s both a neurobiological phenomenon and an institutional failure. I’m talking about the malady—and the misconception—of “mom brain.”

When women invoke “mom brain,” they’re typically describing the experience of feeling scattered, distracted, forgetful, or disorganized as a result of being pregnant or having children. It’s frequently used as an apology (“So sorry I left my keys in the front door! I was juggling the groceries and our toddler! Mom brain!”). Obviously, parenthood comes along with sleep deprivation, especially in the newborn phase, and losing track of time or tasks is an expected side effect. There’s also evidence that pregnant women undergo shrinkages in the volume of gray matter in their brain that may be permanent, though many experts consider those shifts to be more of an adaptive “pruning” than a dulling.

Research has also shown that the brains of fathers and nonbiological parents change with caregiving experience, but one never hears about “dad brain”—there must be some kind of miraculous dad hormone that makes them immune to the affliction. And even though many neurobiological changes are beneficial, the connotations of “mom brain” are almost always negative. Pop culture is full of the stereotype of the harried, forgetful mom—like Kate McCallister from Home Alone, forgetting her youngest child in the chaos of trying to get out the door on vacation with four others. Mothers in real life use “mom brain” as an explanation or to apologize for when they drop balls or mismanage things on their to-do list. But much of the time, what’s really happening is that mom brains—like all other brains—short-circuit when they are overwhelmed.

In fact, “a lot of the ‘mom brain’ is just toxic stress … because of how much shit we are carrying, how much cognitive labor we’re doing,” Eve Rodsky, the author of the division-of-labor guide Fair Play, told me. Even before the pandemic, women were already doing two hours more daily housework than men. According to one survey, the majority of moms in mixed-sex relationships reported doing “more than their spouse or partner when it came to managing their children’s schedules and activities.” The pandemic only made things worse. Data show that in the early months of the pandemic, mothers who had previously been doing the majority of the household labor somehow took on even more, and in another study nearly half of parents reported an increase in stress. One study published in the Journal of Family Psychology found that time spent doing chores was linked to higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol. Furthermore, the higher the share of the housework someone was doing, the slower that cortisol went away. “To whatever extent we expect the household to be women’s domain, then that sort of extra stress burden is going to be disproportionate,” Darby Saxbe, the lead author on the paper and a University of Southern California psychology professor, told me.

This was roughly my own experience: The start of the pandemic coincided with the birth of our daughter, which was an extraordinarily stressful time. Since then, my husband has gone through two years of an internal-medicine residency at Walter Reed while I work from home full-time and have ended up managing the bulk of our domestic and parenting responsibilities. One time, when I flaked on a (luckily low-stakes) item on my to-do list, I took stock of everything else I had been worrying about that week: working my full-time job, solo parenting for days at a time while my husband worked, making calls to clinics to try and get help having a second baby, chasing down a package delivery that had been sent to the wrong house twice, going to the grocery store, getting our dryer vent fixed, troubleshooting our Roomba. The list goes on. That kind of multitasking is exhausting, and it’s no wonder that when things get really busy, I start dropping balls. When I’m that stressed, I also sometimes suffer from restlessness, panic attacks, and GI distress. I have to stop myself from saying I have “mom brain” when I can’t keep up with everything. I should be demanding the help I so clearly need, but between my husband’s nonnegotiable schedule at the hospital, my own fear of becoming the stereotype of a nagging shrew, and my anxiety around overextending our family financially by trying to outsource, that’s much easier said than done.

Jessica Calarco, a sociology professor at Indiana University, told me she believes that what we think of as mom brain “is a product of the unequal burden that we have placed on women to do both the physical caregiving for children and also the logistical and mental work of caring for a whole household.” This is a particularly taxing psychological burden, by nature amorphous, impossible to schedule, and happening in the back of your mind 24/7. It’s things like noticing which groceries are running low and knowing what food the kids will eat, or being the one who plans family vacations—and makes sure everyone wakes up on time to make the flight. “The cognitive labor of running a household is as intense as running a Fortune 500 company,” Rodsky said. And her research supports this: Qualitative data from interviews conducted by Rodsky’s team from 2016 to 2018 revealed that, among 200 mothers who were managing more than two-thirds of the “conception and planning” of their household tasks while also working for pay, every single one had a physical manifestation of stress, such as a flare-up of an autoimmune disorder or insomnia.

Overwhelm can affect people’s psychological and physical condition. Chronic stress can trigger major psychiatric disorders, exacerbate cardiovascular strain, and have consequences related to poor birth outcomes. “There is absolutely reason to be concerned about the health of women exposed to chronic stress,” Christin Drake, a psychiatrist at NYU Langone, told me. Although “there are some important differences between women living in extremely stressful conditions like poverty and lack of safety and those experiencing stresses related to big jobs and limited child care, there is likely some overlap in the processes impacting these groups.” And for those who are overwhelmed by household responsibilities, while also experiencing other intense stressors like poverty, the effects could be even worse. When our culture dismisses “mom brain” as a punch line, it is abdicating responsibility for the overwork women are experiencing and its effects on their health.

While a little joke now and then is hardly responsible for such a complex problem, the phrase mom brain subtly sets mothers up to think there’s something wrong with us or one another, Lauren Smith Brody, the author of The Fifth Trimester and a co-founder of mothers’ rights collective Chamber of Mothers, told me. “In reality, there’s nothing wrong. We just are working in systems that don’t support us.”

Mothers don’t have to live like this. Paid leave, for example, is widely shown to not only benefit the birthing parent while they recover from a physical trauma and adapt to their new responsibilities; it also sets up non-birthing partners to be more involved in child-rearing in the future. If two parents in a household take paid leave, that time allows the family to set a healthy precedent for division of labor. A number of experts I spoke with mentioned that expanded access to postpartum health care could relieve some stress. (“Anything that makes a woman feel like she’s still the boss of her body elevates feelings of competency,” explained Kimberly Bell, the clinical director of a nonprofit in Shaker Heights, Ohio, that offers support and education for early childhood development and families). Communities can establish mom groups where mothers can find support and understanding. Partners can help by stepping up and improving their commitment to splitting chores. By treating mothering like an individualistic endeavor instead of a public responsibility, “we’re setting up mothers to fail,” Saxbe told me.

“Mom brain” isn’t some irreparable, irreversible symptom of motherhood. It’s a symptom of a society that doesn’t support mothers even as they contribute trillions of dollars worth of unpaid labor. “We are putting women at harm in terms of putting all these expectations on them,” says Sinmi Bamgbose, a reproductive psychiatrist in Los Angeles. “Mom brain” shouldn’t be something accepted as the status quo. Moms “please everybody, take care of everyone’s needs,” Bamgbose says. “I think they are breaking.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.